Church

Church

History

History

Sutphin

Sutphin

Star Ledger Article

Star Ledger Article

Slave who took his master's place in the Revolution gets his due

Wednesday, February 26, 2003

BY ELEANOR BARRETTStar-Ledger Staff

The life of Samuel Sutphen might qualify as a quintessential American profile in courage -- if only anyone knew who he was.

A young slave living in Branchburg, Sutphen fought bravely in some of the most famous battles of the Revolutionary War, spent many nights on patrol in frozen fields and was injured by gunfire, all for a promise of freedom if he fought in his master's place and returned to him after the war.

Though Sutphen lived up to his part of the bargain, freedom would elude

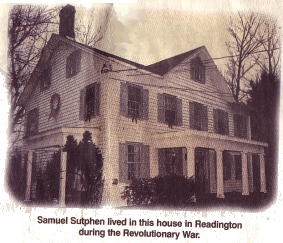

him. Considering him too valuable to be let free, his master, a

Readington tavern owner, reneged on his promise and sold Sutphen to

another.

Though Sutphen lived up to his part of the bargain, freedom would elude

him. Considering him too valuable to be let free, his master, a

Readington tavern owner, reneged on his promise and sold Sutphen to

another.

It would be some 30 years before freedom finally came.

Believing so strongly that the story of Samuel Sutphen must be told, two Brancburg historians have devoted more than 10 years to research his life. They've pored over original Revolutionary War-era pension applications, scoured the libraries of Rutgers and other state institutions, and delved into the collections of public and private sources in an effort to piece together one man's life.

A recent article on Sutphen in New Jersey Heritage magazine attracted national attention, and last year the New Jersey State Historical Commission awarded Susan Winter and William Schleicher $15,470 to continue their work. In 2001, the Somerset County Cultural and Heritage Commission gave Schleicher an award for educational leadership.

"His story just grips your heart. It's a story filled with drama: He was sent away on military expeditions far from home, he could have just kept going. Instead, he came back, and he was swindled so many times until he finally bought his own freedom with pin money he'd saved," Schleicher said.

"It's a story that needs to be told," he said.

Schleicher and Winter's work has not gone without notice by historians on the county and state levels.

Mark Mappen, executive director of the New Jersey Historical Commission, said if it weren't for amateur historians such as Schleicher and Winter, many important links to the past would have been lost.

"It's a wonderful thing that they've opened up a new chapter in New Jersey history," Mappen said. "They've given us a moving account of a brave African-American who contributed to the cause of independence."

Schleicher and Winter began to unearth the amazing life of Sam Sutphen in 1991, shortly after they helped found the Branchburg Historical Commission. They found in the township's historic documents a yellowed, early 1900s copy of the Somerset County Historical Quarterly, which told of how, in 1776, Sutphen was sold to tavern owner Casper Berger and agreed to go to war in his stead.

"Captain (Matthias) Lane agreed to take me in Master's stead, as a soldier, and I was willing that I might be a free man when the war was over," said Sutphen years later in a pension application transcribed by Nicholas C. Jobs, a justice of the peace for Somerset County.

The first real action Sutphen saw was in August 1776, in the thick of the fight of the Battle of Long Island, where 20,000 British soldiers sought to take over the New York Harbor. Many Continental soldiers were lost, but Sutphen was among those who retreated uninjured.

With some skirmishes between, Sutphen found himself on Jan. 3, 1777, marching up the Raritan River to fight in the Battle of Princeton, where he helped carry an injured officer home.

Not long after, at the Battle of Millstone, Sutphen led his fellow militiamen in crossing the freezing, waist-deep Millstone River to defeat a foraging party of British soldiers who had plundered old Van Nest's Mill.

"They had plundered the mill of grain and flour, and were on their way back to Brunswick, but had not got out of the lane leading from the mill to the great road," Sutphen said. "We headed them in the lane ... the drivers left their teams and run. We took about 40 (of their) horses and all the waggons (sic).

"From the time of the Battle of Princeton, I was constantly on guard duty. I performed at least three to four months of duty in this inclement season -- hoping the time of my freedom was not far off," Sutphen said.

Sutphen returned to battle in 1778 at the Battle of Monmouth and would soon after go on to survive an ambush of 800 Loyalists, Tories and Iroquois Indians near Elmira, N.Y.

Next he went on to West Point, where a hand-to-hand combat resulted in two shots to his right leg, an injury that left him scarred and lame for life.

"One cold night, when the snow was knee deep, as I was standing sentry, a party of Hessians and Highlanders, who had crossed the river on the ice, came upon us by surprise," Sutphen said.

"I hailed the first I saw, and he giving no answer, I fired by moonlight and saw him fall .... I received a bullet upon the gaiter of my right leg, and both bullet and button were driven into the leg, just above the outer ankle bone ... In the same affair, I received a wound just above the heel, as high as the ankle, which appeared to be a cut."

At the war's end, Berger renounced his pledge of freedom and instead sold Sutphen to Peter Ten Eyck of North Branch. Area residents were incensed by the news, and officers under whom Sutphen had fought tried to pursued Berger and Ten Eyck to let Sutphen free. But they had no success.

"I believed the white man's word, hoping to be free when the fight was over. I took no paper to show the bargain, but trusted to my master," Sutphen said in his pension appeal years later.

Sutphen, described in government papers as the husband of a "free wench" Caty and father of young Samuel, was sold several more times before he was purchased by Peter Sutphen -- whose surname he adopted. By 1805, Sutphen paid for his own freedom with money he earned selling fur and the skins of rabbits, raccoons and muskrats.

He moved his family to the Liberty Corner section of Bernards Township, bought a 7- acre farm and attended Basking Ridge Presbyterian Church, where Sutphen became known as a "professor of religion."

In the latter years of his life, Sutphen began another battle, this time with the United States government over his right to receive a war pension. Too old to work for a living, he turned to a source of funding that others who fought in the Revolutionary War were eligible to receive.

"Until within a short time, I have been able to feed and clothe myself and my aged wife from our labor, but now in my 87th year, I find my working days are ended," Sutphen said.

"If I can receive a pittance, which I believe I have faithfully and honestly earned by my Militia served in the war, fighting for the white man's freedom, it would gladden my old heart and my wife's."

After five appeals, and five rejections, the New Jersey Legislature took matters into its own hands -- requesting all of Sutphen's pension appeals from Washington and passing an act "For the Relief of Samuel Sutphen of Somerset."

Winter and Schleicher say they hope the pending biography will inspire Hollywood to make a movie on Sutphen's life. But their primary goal is to spark interest on the little-known role African-Americans played during the Revolutionary War -- the Militia Act of 1777 permitted the enlistment of "all" effective men -- and to intrigue even non-history-loving people, as they learn of Sutphen's tale of courage and betrayal and of the battle for freedom for himself and a nation.

Giles Wright, director of the state agency's Afro-American History Program, said there is no more comprehensive account on Sutphen's life than the one arrived at by the two Branchburg historians. The story, Wright said, not only illustrates a brave man of war, but brings to light the role of African-Americans during the American Revolution.

"It's something many might not be aware. Black people played a part in the very struggle that brought this country into being," he said.

The work hasn't been easy, as Schleicher and Winter have pored over historical documents gleaned from state and local libraries, archives and public records, and Revolutionary War pension applications -- in which Sutphen's own voice echoes clearly.

"I have told the story of my service in the war, according to the best of my remembrance and belief," Sutphen said. "I may be wrong in dates and perhaps sometimes in the names of places and officers, but before Him who is to be my Judge, I can declare confidently that my services have been done to the full extent of my story."

Sutphen died on May 8, 1841. No record of his burial place has been located.